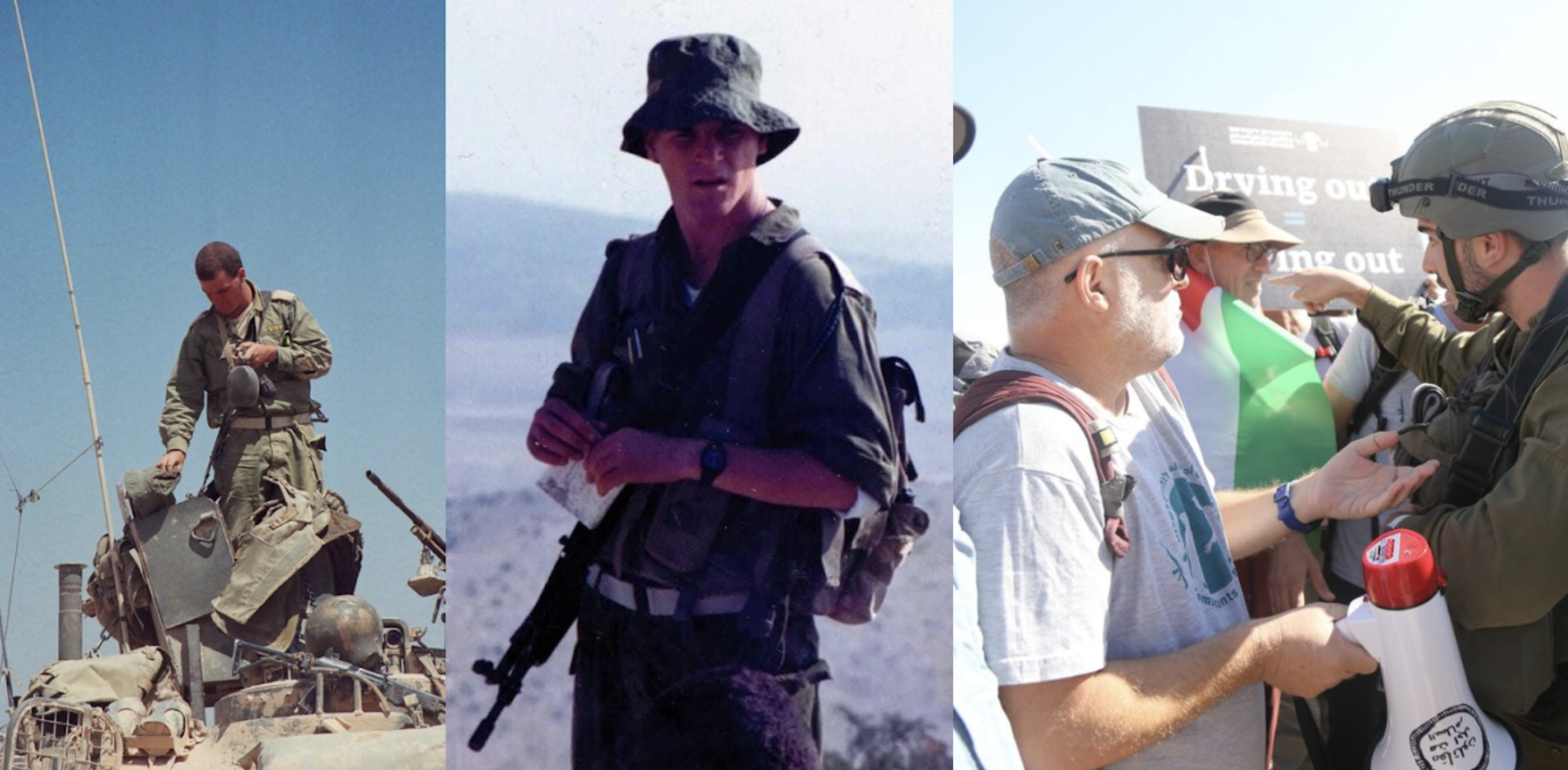

Interview with Chen Alon (Israeli) from the Combattants for Peace organization

By Naia Gerigk Lopez & Louis Baud

You mention having been exposed to your father’s trauma from a very young age. Would you say that such experiences create transgenerational trauma?

Absolutely. In Israel and Palestine, I believe that the majority of generations experience a form of transgenerational trauma. For us Jews, this pain began with the Holocaust and was carried down through the generations. And for Palestinians, it is the 1948 Nakba tragedy, which caused them to terminally lose their homeland with the vast majority being expelled from the territory.

As a result of the massacre and expulsion, people are drawn into this cycle of violence. It establishes a narrative that makes people fight to enter the violent circle, which is where the justification for violence begins. We are all prisoners of this transgenerational trauma, leading us to normalise violence.

How did you experience the role of a devoted father in contrast to your role as a soldier?

One of the main ideas that I describe in my personal story is how this narrative of dehumanising enemies is constructed. We dehumanise our opponents to the point where when you wander through enemy land, you no longer see human beings, but rather terrorists or militants. And when you see children and babies you see future terrorists.

Now I’m perplexed by the ability of the system to create this mentality, or even indoctrination for me as a soldier, that claims they are all the same. They are all our enemies, they all want to kill us, none of them accept us, and so on. It really affects how we approach missions. For instance when invading a house, and seeing terrified women and children peeing in their trousers, you see them but don’t see them all at the same time.

Today I am unable to explain how I can be a devoted father, a compassionate human being and so merciful to my children, while being blind to Palestinian children, the enemy’s children. It’s a major question for me. It is a mystery today, a mystery that I used to embody. Today when I see a baby or a child in Gaza, Turkey or Geneva, I see them for what they are, a baby and a child. However, on the battlefield, I was somehow not able to see them.

I believe having children of my own, enabled me to undergo a transformation, because I couldn’t deny their humanity. I could no longer see them as terrorists. When you have your own children and are no longer 19 years old and a soldier, it becomes more difficult to deny it.

Why do you say that the dehumanization of others, such as the palestinian children, leads to the dehumanization of oneself?

It’s a quote by Nelson Mandela, who said that it is inevitable that you dehumanize yourself when dehumanizing the other. For me this is no theoretical concept, I truly feel it in my flesh and bones. Dehumanization in this context is not a choice.

How did you react emotionally when you discovered that the “target” of a mission turned out to be a child?

I was an officer in a tank unit, so we were trained to use tanks for regular war, not these military missions. We were called to deploy to Gaza (1990), and we did our first patrol in the area, switching with our predecessors.

As we drove into a small town in the Gaza strip, a cocktail molotov was thrown at our jeep causing it to be inflamed. We had no choice but to evacuate the vehicle. A few nights later, while we were responsible for this region, we received a call telling us that the identity of the one who threw the molotov cocktail was known. My team and I were asked to arrest him. So, very late at night we navigated our way to a specific house where I met someone from intelligence who knew the responsible person. Therefore it was sort of a justified military mission.

We went to the house and I placed my soldiers to block all the entrances as we would do in the military. We entered, prepared with our guns, and searched for the terrorist. Someone was taken out of his bed. He must have been 9 or 10 years old. The man holding him affirmed that he was our guy. There was silence among us. A few women begged us not to take him. We left the house, carried the child out and placed him in the car to return to the military base.

I had a very heavy heart afterwards. I rationalized that it was a mission and I was simply obeying my orders as an officer with soldiers and responsibilities. At some point during the night, soldiers called out for me, wanting to discuss the incident. They questioned me saying “what was that? It was a child!”. I explained that the army has no right to pick and choose missions. We must obey. The people above us know what they are doing and this is how the army functions. However they did not accept this. I continued to explain that we were simply protecting our land because otherwise they would keep throwing these cocktail molotovs and burn our children. I was justifying something even I could not believe.

It took me many years to understand that I don’t stand by such missions and that I only did it because of the narrative I learned by heart. But I didn’t refuse to kidnap that child from his house. And I did it many times, a lot of killings while I was in the occupied territory. It took me many years to stand up and refuse to justify this. It is illegal to kidnap someone from their house without a legal order. In Israel, the laws forbid doing that. However in the occupied territories none of these laws are applied.

What message would you like to convey to young Israelis entering the army today?

Don’t join the army. Israel may have the right to protect itself, the right to exist and the right to have an army. However the occupation has nothing to do with the security of Israel. The violation of the human rights of Palestinians between the river and the sea has nothing to do with security.

I don’t have a particular message as I think that people should think for themselves. Therefore my advice is to think critically and not allow anyone to convince you that this is justified under any circumstance.

How do you respond to critics who say that refusing to serve your country is a cowardly act?

Well I spent a long time in the military. 3 years were the mandatory military service, and 1 additional year as a volunteer because I became an officer, and then 10 years in reserve forces, meaning one month a year during 12 years. In total I worked in the military for 5 years over the course of 14 years. I reached the rank of major in the tank medallion. Very few people can call me cowardly in the Israeli context, in terms of war and military.

However, today I believe that stepping down and standing for human rights takes much more courage than fighting in the military. This courage is different because you need to fight against yourself.

I have received many criticisms; I’m a coward, I’m betraying my people, betraying the holocaust, betraying my grandfather. There is no critique that I have received that I did not already hear in my head. There is no voice that could be more harsh than my own doubts and voices. Now I am immune from all these misogynistic discourses… about what it means to be a man, what it means to be brave.

What do you believe is the value of both Israelis and Palestinians mourning together at your joint memorial ceremonies?

I directed the first ceremony we ever had. Fourteen years ago in 2006, there were 80 people in a small french theatre in Tel Aviv. Two years ago we hosted it in the biggest park of Tel Aviv with 15 000 people. I observed the evolution of this ceremony.

Its main success is that it answers the needs of Israelis and Palestinians to reconnect through pain. It has some kind of code that is naked from colors, symbols and images. It is just pain, sorrow and grief, naked on stage, and somehow this tremendously unbearable pain is hopeful. Because all the ppl on stage, Israelis and Palestinians are standing together and saying they lost the dearest thing to them, yet they are still committed to humanity and justice.

How can we bring hope amidst so much tragedy?

Through responsibility. There is knowledge that can emerge from violence. Many use it to perpetuate more violence. However what is truly admirable, is those who are able to transform this knowledge into responsibility. That is what we are doing. We are committing to non-violent peace and to justice for humanity. While we don’t use the word religion, it’s very spiritual. In dark times, staying in contact with your loved ones who are experiencing similar pain can be very helpful. Simply getting an acknowledgement for your existence and your pain gives me hope. It reconnects me to the responsibility that we have together to maintain this flame of my national community.

For further information : https://www.cfpeace.org/